Since I write and lecture mainly about international relations and twentieth-century diplomatic history, most of my reading is related and leaves little time for fiction. But this summer I decided to relax with a thriller or detective story to get my mind off the fast-paced disasters taking place in the Middle East, Ukraine, North and West Africa, and the slower-paced ones brought on by environmental degradation, organized crime, pervasive corruption, and political deadlock. Maybe fiction could provide distraction and even, perhaps, restore some remnant of the optimism I felt about the world a quarter century ago when the Cold War ended, Europe united, and the world was at peace–even, for a time, in Palestine.

A Raymond Chandler private-eye novel from the 1940s was the first volume I took from the shelf and brushed off a layer of dust. I gave it up after 50 pages or so. The tough-guy talk rang false, the clichés grated, the characters seemed to be competing in a contest to be crowned the “most repulsive,” and the formulaic plot lines were by now so familiar that they held no surprise.

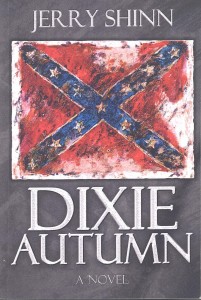

And then, a copy of Jerry Shinn’s Dixie Autumn showed up in the mail. Rebecca grabbed is first and was soon engrossed. In fact, it kept her up late that night. When she finished it the next day, she handed it to me as a “must read.”

Why? Well, first because it was a compelling story, full of memorable characters and unexpected twists but never stretching for credibility. Second, because it is about a part of the American South close to where Rebecca and I grew up (she in Middle Tennessee and I in Piedmont North Carolina) and it is mainly about a time when we were away. When the Civil Rights movement took on momentum in the South in the 1960s, we were out of the country through the entire decade except for a few weeks of home leave every two or three years. When we returned to live in Washington, D.C., in the early 1970s, the country was a different one from the one we knew when we left Washington for Austria in 1958. Of course, we knew about the major events that occurred in the sixties. Who wouldn’t know about the civil rights struggle, regardless of where they were in the world, if they followed the news? But following news about events, even in familiar locales, is not the same as living through them.

Dixie Autumn is set in a small town in Piedmont South Carolina. Most of the action, as recalled by the main character four decades later, takes place in October, 1962, after the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools violates the Constitution but before that decision was implemented. The main character, who narrates the story, is a reporter for the newspaper in Columbia, the state capital, who returns to the town where he grew up to investigate the murder of a childhood friend, killed in a bomb blast at her parents’ home. There is every reason to suspect that the bomb was set by some “redneck” white supremacist in the neighborhood. The narrator sets out to identify the murderer and eventually does, though not before driving up several investigative blind alleys.

Dixie Autumn was an exciting read. I had trouble getting anything else done once I started it. But it was not like many other thrillers I have read for diversion. They may entertain me, but when I finish them the magic is gone. After a few days, I will have forgotten the title and probably also the names of the characters and how plot turned out. Maybe even the author. Absorbing while it lasted, but then it’s all over.

This didn’t happen with Dixie Autumn. The principal characters stay with me; I can almost see them with my mind’s eye. It allowed me to experience the atmosphere of events at home at a time when I was sitting in a cubbyhole in the American Embassy in Moscow translating Nikita Khrushchev’s letters to President John Kennedy during the Cuban missile crisis. But the meaning for me was broader and deeper than that: it provided a reminder of the hazard of drawing quick conclusions based on assumptions that may not be valid, the complexities of right and wrong during times of confrontation and tension, and the fact that the most careful and ingenious plans can have precisely the opposite effect from that intended when they are carried out.

Cousin Jerry, you deserve congratulations! Could you have another one ready for us by next autumn?