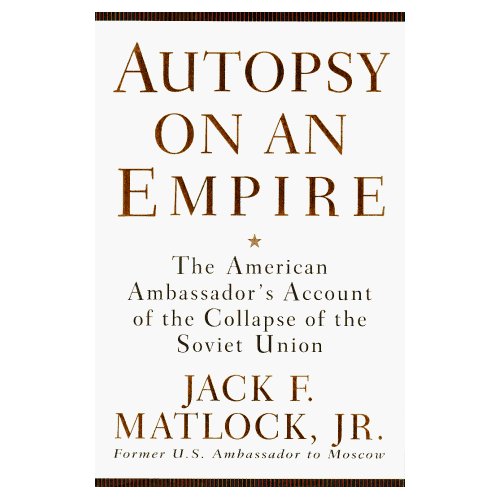

Autopsy on an Empire:

The American Ambassador’s Account of the Collapse of the Soviet Union

by Jack F. Matlock, Jr.

As the United States ambassador to Moscow during the Gorbachev period and Ronald Reagan’s full-time go-between with the Soviet leadership, Jack Matlock couldn’t have been in a better position to observe the collapse of the Soviet Union. A career diplomat, fluent in Russian, with a scholarly grasp of Russian history and culture, Matlock served in the USSR for much of his career and knew the men in the Kremlin well. He had traveled widely in the Soviet Union—more widely, perhaps, than most Soviet officials—and had seen firsthand the discontent in the captive republics. Matlock was uniquely placed to anticipate and interpret the process as it unfolded. Yet, even he was surprised by the speed and finality with which the rickety empire gave way.

Though Matlock writes that a definitive version of these events may never be told, it is unlikely that a more intimate and knowledgeable account of the rise and fall of Gorbachev and the collapse of the Soviet empire will ever be written. A first-rate historian and a powerful writer, Matlock offers new insight into the contrasting policies and personal approaches of President Reagan, who dreamed of changing the Soviet Union, and President Bush, who witnessed a collapse he tried to prevent. Drawing on frequent private meetings, he explains the agenda behind Reagan’s “evil empire” speech and describes how Gorbachev developed his program for reform, and why he failed.

Autopsy on an Empire contains many new revelations—details of the plot to oust Gorbachev in August 1991 (including Bush’s inadvertent impact on the plotters’ timing), accounts of infighting within the politburo, and insight into the true positions of American policy makers. It is a monumental work of observation and scholarship, arising from vast personal experience and more than thirty years of reflection. Matlock is a superb writer, and Autopsy on an Empire will be the classic account of the fall of Soviet communism.

Translations

Chinese edition |

Russian edition |

Questions Welcome

Questions and comments are welcome from registered participants who have read the book. (I don’t have time to explain again something I have explained in the book.)

During the coup, when Mayor Popov told you about what was going on, Gorbachev didn’t take you seriously, why do you think he didn’t listen?

My guess is that he thought we were reporting to him something he already knew: that some army colonels were grousing that he should be removed. You see, I did not name the people Mayor Popov had listed. I told him we had a report that we could not confirm but it was more than a rumor: that a conspiracy was being mounted against him. I did not think I should finger people when we did not have hard evidence they were plotting. But it turned out that they were the ones that organized the attempted coup in August.

I haven’t read the book in a long time, I wonder if I can find an audio version of it somewhere to listen to it. There were many officials involved in the coup atteempt. Tell me Jack, who do you believe is to blame for the coup attempt failing so badly?

Unfortunately, there is no audio version of Autopsy. (I offered to record one, but the publisher thought there was not enough demand.)

The coup attempt failed for many reasons, but most of all because circumstances had changed and people were willing to oppose it peacefully. The armed forces were unwilling to fire on an elected Russian president (when Yeltsin challenged the coup leaders) when an unelected junta tried to give orders. Also, the coup was poorly planned, mostly at the last minute. One reason for this may have been that the organizer, KGB chairman Kryuchkov, realized that he had a leak when Moscow Mayor Popov warned me about the coup, and President Bush mentioned to Gorbachev on a telephone line maintained and monitored by the KGB that our information came from Popov. At that point, Popov later surmised, Kryuchkov had to do his planning in such a tight circle that he was unable to get the whole thing properly set up.

One of the ironies of history. It shows how many important things are caused by, or affected by, chance.

Jack. According to Gorbachev’s memoirs, the coup went wrong for several other reasons, and many of the people involved ran into problems. Example: for some reason, they forgot to have Yeltsin arrested. Also, Marshal Yazov and Vice President Yaneyev went on a drinking bindge at one point, and Prime Minister Pavlov was hospitalized with blood pressure problems.

Gorbachev has been reluctant to recognize that he made a mistake in rejecting our warning. He still feels that Moscow Mayor Popov was trying to undermine him (which I do not believe is true).

Of course, something as big as the failure of a coup attempt has many causes. But the lack of preparation certainly contributed to the failure of the attempted coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. One reason there was so little preparation may have been that the coup leaders learned that they had a leak and therefore so restricted knowledge of their plans that they could not secure the cooperation of many people they needed, such as the military commanders.

I go into many of these details in Autopsy on an Empire.

Gorbachev shouldn’t have taken Pavlov as PM, the guy had some crazy ideas about American banks did he not?

I have several comments about Pavlov in Autopsy on an Empire. He was boastful, dishonest, and ultimately betrayed Gorbachev by joining in the coup effort in August, 1991.

If you were Gorbachev, what would you have done if you heard about a coup attempt. I would’ve taken it seriously, and tried to figure out who was involved in it.

Of course, he should have paid more careful attention. But so many false rumors were going around that he must have thought that our warning was based on one of them. A day later, when President Bush told him on a telephone call that our information came from Moscow Mayor Popov, he thought that Popov, whom he considered a political rival, was just making trouble.

If Gorbachev hadn’t picked Pavlov, who else could he have picked as PM?

Liberals had recommended Sobchak, the mayor of Leningrad (the name then being changed back to St. Petersburg), and others thought that Arkady Volsky would be best. Both would have been loyal prime ministers to Gorbachev and would not have joined the coup plotters in August, as Pavlov did. A more far-out option would have been to name Yeltsin; it the latter had accepted it would have removed his incentive to lead Russia out of the union. But Gorbachev was too suspicious of Yeltsin for him to have thought of such a radical step!

Who did Gorbachev have in mind for replacing Yazov, the KGB chairman, and some of the other hard-liners?

I d0n’t know. I never asked him, and I’m not sure he had made up his mind when he told Yeltsin that he would change them when the Union Treaty was signed. Primakov would probably have been a candidate for KGB chairman.

I’ve read in Gorbachev’s memoirs that he loathed Ceausescu of Romania, but I’m certain he felt the same way about many of his other Eastern Block allies, especially the leader in East Germany.

Yes, Gorbachev tried to push Honecker to initiate reforms, but Honecker refused. Meanwhile, when Gorbachev visited East Berlin, the crowds gathered and shouted, “Gorby, Gorby, Gorby!” Chernyaev, his foreign policy assistant, says that this had a deep affect on him and caused him to let Honecker know that he would not use Soviet troops (which were stationed in East Germany in large numbers) to save him.

I remember reading about the Gorby part in his memoirs. There were a lot of people involved in the coup, the KGB Chairman, the Secretary of Defence and his Deputy, Gorbachev’s chief of staff, the Vice President, the Prime Minister, and more.

Yes. I described it in detail in Autopsy on an Empire.

Gorbachev’s cabinet was interesting. Ryzhkov had been head of the Soviet Federal Reserve, Gromyko had been the Secretary of State for almost 30 years, and so on.

No, Ryzhkov was never chairman of the State Bank. He was an industrial manager in the Urals before he was transferred to the CC Secretariat in Moscow. He and Gorbachev were assigned by Andropov to plan secretly some economic reforms.

Ryzhkov’s successor, Pavlov, had been Minister of Finance but not chairman of the State Bank. I recount in Autopsy how he tried to embarrass the Chairman of the State Bank in my presence.

Gromyko was indeed the longest serving Minister of Foreign Affairs.

What’s your opinion on some of the Soviet Defence Ministers? In one book, the author says Marshal Yazov was only fit for a division command. One of my favorite Soviet Secretaries of Defence is going to be Zhukov.

Zhukov was a great commander during World War II and Eisenhower had a lot of respect for him. Akhromeyev was a more impressive military leader than Yazov, but he too supported the coup against Gorbachev, then committed suicide when it failed. But he was an impressive, and very likeable human being. He and Bill Crowe, then our chairman of the JCS, became great friends.

Any Soviet military officers you thought were some of the worst based on how they commanded their troops?

A Dutch student has asked the following question by email:

“I am making a magazine about science, history and culture. In it, I would like to make a kind of ‘poll’, about the dissolution of the Soviet Union; however, it will not be such silly multiple-choice poll, in which one cannot explain the answer. For the ‘poll’, could you help me, by answering the following question?

“What do you, ‘personally’, think was the most important, significant cause which led to the dissolution, or ‘collapse’, of the Soviet Union? (it may be either long-term or short-term).”

Answer: There were many causes for the break-up of the Soviet Union, but the fact that it had been created by force and ruled as a one-party dictatorship made it difficult to become responsive to its people’s needs and desires. Nations that had been subjected to the Soviet empire—for it was an empire—naturally desired their independence. The economy had been designed to produce mainly for the government and military and not for the people as a whole, and this weakened support for the Soviet Union. These conditions undermined the authority of the central government even though President Gorbachev was trying to make it more open and democratic. In August, 1991, a cabal of senior officials tried to take power from President Gorbachev, and though they failed, they fatally weakened the Soviet Union. By December, the leaders of three key republics (Russia, Ukraine and Belarus) decided to replace it with a loose association. From that point, there was no way to prevent its collapse.

Two important things to remember: (1) The Soviet Union broke up because of internal causes not pressure from abroad; and (2) The Cold War ended before the Soviet Union broke up. It was not a victory of either side, but a negotiated end that was in the interest of both. The end of the Cold War gave President Gorbachev the possibility of trying to reform the Soviet Union, but forces inside the country made this ultimately impossible. Most Western governments, including the American government, tried to help him keep the country together as a democratic federation, but conditions in the Soviet Union made that impossible.